“Love has the power to inspire students to seek after knowledge, love can unite the teacher and student in the quest for knowledge, and the love of learning can even empower students to challenge knowledge thereby pushing its limits” Daniel Cho, 2005. In his book titled “Love as Pedagogy”, Tim Loreman argued that love is a product of, and a necessary element to successful and meaningful teaching and learning. But what is love? In the fa’aSamoa, alofa (love) extends to notions of compassion, caring, generosity, and consideration, which is closely related to fa’aaloalo (respect). Fa’aaloalo encompasses the values of courtesy, politeness, and pleasantness, as well as reciprocity and gift giving. Here at TYMS, we simply call it ‘going above and beyond'. Kindness and empathy are elements of love. Aristotle in his Rhetoric, described kindness as helping another in the absence of tangible rewards for doing so. The Dalai Lama asked his followers to pursue a ‘policy of kindness’, which he connects with notions of warm-heartedness and helping others. Empathy on the other hand, is described by Professor Roslyn Arnold as “an ability to understand the thoughts and feelings of self and others. It is a sophisticated ability involving attunement, decentering, and introspection: an act of thoughtful, heartfelt imagination”. Kindness and empathy are at the heart of this notion of love as a pedagogy. Acts of kindness bring us close to one another, and it is in this closeness that we are able to develop a mutual understanding, leading to empathy. As Daniel Batson and his colleagues have shown in their studies on altruism and empathy, when we understand and identify with another, we are more likely to help them. Meaningful learning occurs when teachers and students understand and identify with one another. Empathic teachers are more likely to understand their students to a greater degree, and are perhaps more sensitive and able to respond to their strengths and needs in areas ranging from academic, cultural, and emotional, to behavioural. Similarly, empathic students might be more adept at responding to a teacher, and in drawing out learning through more perceptive responses to learning situations. Fostering and cultivating kindness, empathy, and love in the school environment, is thus a worthwhile investment in the educational success of our children. One TYMS mentor has spent the past 4 weeks in three West Auckland schools, cultivating kindness, a positive attitude, respect, integrity, courage, teamwork, communication, and honesty, in 3 groups of 8 young boys who have been flagged by their teachers and school social workers as ‘at risk’. This strengths-based approach has resulted in positive engagement from all involved - the students, staff, and families. One task required the young boys to carry out one random act of kindness a day, and to record this in their notebooks. These young boys did not stop at one act. Instead, they carried out multiple acts of kindness, which extended beyond the school environment to their homes and community. One boy helped an elderly lady at the bus stop carry her groceries, and another said hello to his neighbour in the morning. When one young boy told the mentor that he couldn’t think of an act of kindness to complete the previous day, another member of the group jumped in and said ‘but you gave that boy in class 50c to buy lunch’. To the mentor’s surprise, the young boys also took their notebooks to their teachers, and asked them to write in their notebooks something good about them, or a behaviour that they wanted to see an improvement in. The teachers participated in the activity, and some even bought their own notebooks. Linda Albert suggests that the teacher-student connection is fundamental to a healthy and productive relationship. This connection can be fostered with her Five A's approach: accept, attention, appreciation, affirmation, and affection. Teachers must put aside their biases and fully accept the student, regardless of their background and perceived flaws. Students must also be given attention in order to feel valued and important. Teachers must also show an appreciation for the good deeds and actions that the students do, no matter how small. Teachers must provide affirmation, by showing an enthusiasm for their students and encouraging them to believe in their own self-value. And affection - can we ever truly feel for and care about someone we feel no affection for? Our mentor has cultivated kindness and empathy in the young boys from these schools, and they have in turn spread this love to their teachers, other students, their families, and the people in their communities. These young boys continue to remain in school, and they have bright futures ahead of them. When we seek the good in young people, we will find good. When we highlight their strengths and build on these, we create kind, empathic, and loving future adults and productive members of society.

0 Comments

Author: Koleta Savaii Physical well-being is central to the fulfillment of our everyday tasks and long-term goals. We need to be in good physical health to be able to go to school or work and to participate in activities with our families and friends. In turn, we feel good about ourselves, we find enjoyment in what we do, and this has spill-over effects to other areas of our lives. It benefits society.

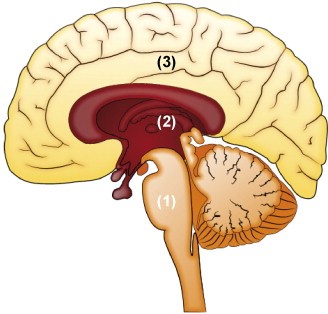

Improving the physical well-being of the young people who come to TYMS is a major goal of our service. We accomplish this through our focus on these two areas: the executive function and social cognition. The executive function and social cognition are associated with the prefrontal cortex which is situated in the frontal lobe part of the brain. The executive function is used to describe the capacity that allows us to control and coordinate our thoughts and behaviours. These skills include selective attention, decision-making, voluntary response inhibition, and working memory. Social cognition focuses on how people process, store, and apply information about other people and social situations. The way we think about others plays a major role in how we think, feel, and interact with the world around us. Puberty, which is associated with adolescence, represents a period of synaptic reorganisation in the brain (think of electrical wires in your computer reorganising themselves). Consequently, the brain might be more sensitive to experiential input at this period of time in the realm of executive function and social cognition. What this means is that, the adolescent brain is at a pruning stage which makes it an excellent time to foster executive function and social cognitive skills, which can last into adulthood. So, where does physical wellbeing come in? Physical activity requires volition, planning, purposive action, performance monitoring, and inhibition – skills associated with the executive function. To successfully adopt or change physical activity behaviour, an individual must form a conscious intention about what activity they wish to adopt (volition), identify the sequence of actions required to achieve the intended activity (planning), initiate and maintain focus on the chosen activity over time (purposive action), compare actual progress with planned progress over time, identify and correct mistakes (performance monitoring), and overcome the temptation to remain inactive or eat an unhealthy diet (inhibition). These are the stages our young people go through when we work with them on improving their physical well-being. The great thing about these skills is that they are transferable to other areas of life where planning, decision making, etc. are needed… like Maths. Research shows that kids who engage in physical activity significantly improve in Maths compared to kids who don’t. To improve social cognition, the literature suggests that accumulating social experiences is crucial for social cognitive processes. While we have a gym on site where young people carry out their exercise regimes, our mentors also spice things up by taking the young people out to parks, swimming pools, and local sports clubs. Given that majority of the young people who come to TYMS face social exclusion in one form or another, taking them out to the community aids in re-establishing their social connections, minimising their experiences of exclusion. When we are surrounded by lots of people, it is a learning ground for our social cognitive processes. We know anger, happiness, fear and joy because we see these emotions expressed on other’s faces or in their behaviour. And we know the boundaries to our own expressions of these emotions because others act as guides, expressing approval or disapproval when we behave or act in certain ways. Social connection fosters emotional intelligence and empathy, which are essential characteristics to being a good member of society. Here at TYMS, our approach to improving our young people’s physical well-being is holistic. It is about good physical health on top of fostering executive function and social cognition skills. These skills combined will enable our young people to reach their full potentials and secure positive futures. Author: Koleta Savaii Adolescents are at a transitional stage – from their high dependence on parents and family to a need for autonomy and independence as they progress to adulthood.

While at this stage the role of the family in the adolescent’s life is secondary to that of the peer group, a close best friend, or a romantic partner, this does not mean family support is no longer needed. Adolescent researchers have established that different types of relationships fulfill specific interpersonal needs. For example, in romantic relationships, adolescents learn the social aspects of this type of relationship from their relationships with their parents and close friends (i.e., intimacy, conflict resolution, trust, empathy, and compassion), while the sexual aspects are learned from a dating partner. For healthy youth and consequently healthy adults, we need to ensure that every one of their relationships are healthy, and that they provide positive learning experiences. The adolescent years are also critical to the formation of one’s identity. At any point in history we will find that the opportunities available to youth for identity formation differ. For instance, for the grandparents of today’s youth, cultural exploration was restricted by geographical boundaries and the only cultures available was that of their families, church and communities. With increasing globalisation and the popularity of social media, today’s youth literally have access to thousands of cultures and opportunities for identification at their fingertips. A multitude of options to choose from can be distressing for any individual. But this can be especially stressful for adolescents whose brain areas that are responsible for executive function tasks (i.e. self-control, decision making) are not yet fully mature. This region of the brain is also responsible for a variety of other functions, its a common reservoir. Therefore, when we exercise self-control, we tax this common reservoir. For example, trying to maintain a healthy weight by exercising regularly and eating a healthy diet, while at the same time controlling the urge to eat unhealthy foods and stay in bed all day is physically taxing on this common reservoir. If it is not replenished (i.e. through positive self-affirmations, glucose consumption), then we are unable to exercise self-control in other areas of our lives (e.g. we procrastinate in our school work, or we over-spend beyond our available finances). Executive function is like a fuel tank that needs to stay filled. Positive self affirmation is one way of filling up our executive function tank. Adolescents are therefore at a stage in their lives where they need all the support they can get to keep them on track. Unfortunately, the availability of adults or other individuals willing to provide help and/or show interest in their problems is very limited. And this seems unfortunate, when an overview of the literature in this area shows clear links between the quality of adolescents’ supportive relationships with such features as self-esteem, suicidal and delinquent behaviours, emotional illness, and negative emotional states. The availability of positive social support is important, but this has to be accessible and of value to the individual. For example, in many Pacific families, gaining an education is highly valued. Generations of Pacific families have left their homelands for this very reason. For many Pacific parents, their motto is “Education is the key to a good life”. They wish for their children a life that they couldn’t experience themselves while growing up, so they push for their children to gain an education so that they can get good jobs to have a chance at the good life. Hence, adults in the community that provide mentoring and academic support is valuable to both Pacific youth and their families. Social support provided by parents and peers is crucial to the health and wellbeing of young people. This resource will not be utilised, however, if the barriers around access are not addressed. Barriers can include individual personality factors (e.g. low self-esteem), culture (e.g. cultural norms/attitudes around help-seeking), and financial (e.g. transportation costs). The availability of a valued resource coupled with the removal of barriers to accessing such resource, is key to ensuring young people are making use of the programs available to them within schools and in their communities. Social support whether it be provided by peers, parents, and members of the community is crucial to the health and wellbeing of young people. Positive adults who show an interest in youth and their problems is sometimes all it takes to keep a young person outside of prison, off the streets, and in school. Author: Koleta Savaii The family is the most important institution in children’s lives.

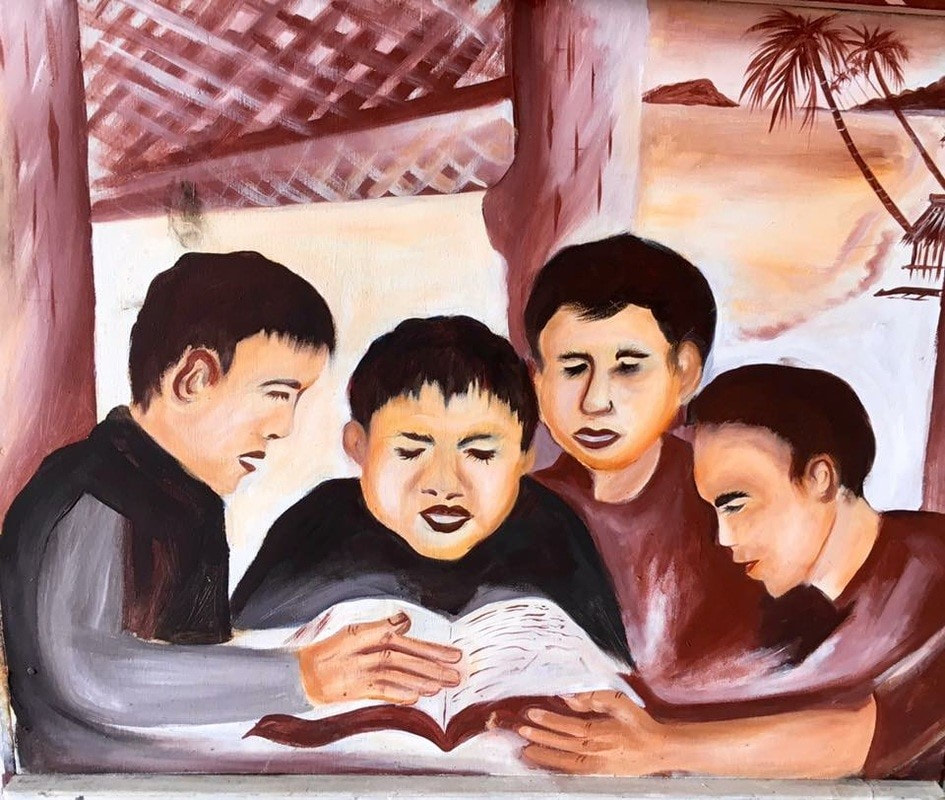

For many of our Pacific children, the family is where language, values, and cultural and religious beliefs are taught and nurtured. A strong family is one where members can depend on each other, where people are treated well, where values are shared and respected and where there is financial security. Just like a well-built fale, a strong family can weather even the greatest storm. Sadly, not all our Pacific families are weathering the storm. A shift in New Zealand’s socio-economic environment has contributed to Pacific communities suffering from cultural erosion, social fragmentation and an increasing loss of identity. This has instigated changes in Pacific family structures and dynamics, including increases in de facto relationships, shifts towards single parenting, and changes in traditional attitudes towards care for the elderly and the young. These changes have undermined our family units and the ways in which family members relate to each other. Many Pacific families are underpinned by cultural values of fa’aaloalo (respect), va fealoao’i (relational boundaries), tautua (service), and alofa (love). When these values are lost, the family can become a place of suffering and dysfunction, rather than sites that nurture strong and vibrant families. When children and young people have strong and healthy relationships with their families, their health and wellbeing increases and they are less likely to be involved in delinquent behaviours. Children are believed to be a tofi (inheritance) from God. The Christian bible teaches us to ‘Train up a child in the way he should go; and when he is old, he will not depart from it’ -Proverbs 22:6. Samoa also has a well-known saying “O le tama a le tagata e fafaga i upu ma tala, a o le tama a le manu e fafaga i fuga o laau” – The offspring of men are fed with words but the offspring of birds are fed with seeds. In the EFKS (Congregational Christian Church of Samoa) tradition, when a child is baptised, all who witness this sacred ceremony (the family and the church community) are endowed with the responsibility of raising the baptised child in the ways of the church and fa’aSamoa (Samoan way of life). Hence the saying: ‘It takes a village to raise a child’. Pacific peoples have a holistic view of the world. This worldview is comprised of the social (people), the physical (land and resources), and thespiritual (God the creator), where individual and collective wellbeing is a consequence of a balance and harmony between these interrelated domains. This holistic worldview is encapsulated in the well-known Fonofale model of Pacific health and wellbeing. According to the Fonofale model, the Pacific self is envisioned as a fale (a Samoan house;right). The fa’avae (foundation) is central to the Samoan fale; a solid foundation ensures the fale will withstand any changes in the weather. Likewise, Pacific wellbeing as envisioned by the Fonofale model, requires a strong, healthy and vibrant family. It is well-established that when children and young people have strong and healthy relationships with their families, their health and wellbeing increases, and they are also less likely to be involved in delinquent behaviours. Good family relationships have spillover effects to other areas of the child’s life, including their education. Significant research in the education sector spanning the past 25 years has demonstrated that family involvement is critical to the educational success of children . Involvement in their children’s educational journey gives parents confidence, as they are able to see themselves as more capable of assisting educators or youth service providers who are working with their children. Inclusion makes parents and families feel valued and appreciated. Inclusion also sees parents as equal partners in their children’s education, and this gives them the confidence to assist with their children’s work and school projects that are to be completed outside of school. Family inclusion in education also sends a message to young people that their school values their parents’ contribution and involvement. All children want to feel pride in their families, and that pride will probably influence how the child feels about him/herself. When a Pacific individual is successful, whether it be in education, sports, or employment, families and communities celebrate together. Success for one individual is linked to family and community wellbeing; accordingly, most activities are carried out with the goal of “contributing to the family good, and not for personal gain”. As such, it is crucial that educators and service providers working with Pacific peoples ascertain the aspirations and expectations of Pacific families, so that their goals are aligned with those of Pacific families, ensuring maximum positive outcomes for the young person. This means a working together in partnership with families, sharing the responsibilities and decisions on the young person’s educational journey from start to finish. At TYMS, we always make a solemn promise to families that we will look after their children as if they were our own. As a provider of programmes aimed at addressing the underlying needs of young people through academic mentoring addressing education needs, values, life skills, physical fitness and cultural identity, TYMS works together with young people’s family and whanau, with the child at the centre. In the Samoan culture, when a precious gift such as an ‘ie toga (a precious, finely woven mat that is a most important item of cultural value in Samoa) is handed over, it is important that the receiver honour the gift. When families hand us their child, they are handing us their most precious gift. It is up to us to look after that gift, and we always make a solemn promise that we will look after their children as if they were our own.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2018

|

What Our Clients Are Saying

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed