|

Author: Koleta Savaii In the media last week, MOE released its review of the Alternative Education sector. In a nutshell, the review concluded that the alternative education has been “largely ineffective”, with suggestions for “a stronger move to help schools keep the most at-risk teens in mainstream classes”.

‘Keeping at-risk young people in school' is exactly what TYMS have been doing since its inception, and we have seen tremendous successes. The results of our 2016 Evaluations Outcomes Harvest revealed that of our total 183 clients, 73% remained in school, 9% returned to school after being excluded, and 2% transitioned into Alternative Education. While we are pleased with these results, our insights and key learnings over the many years of working with our young people and their whānau have taught us that the suggestion to ‘keep at risk youth in mainstream classes’ is not as simple as it sounds for all involved. I had the privilege of catching up with two of my close friends from my undergrad and postgrad tutoring years last Saturday for brunch. Since our tutoring years, one friend is now an Academic and Careers advisor at a South Auckland high school, and the other is a lecturer in one of the University's Certificate Programmes. We reminisced about our tutoring days and the challenges we faced, especially with students who were ill-prepared for university. My lecturer friend told us that not much has changed, "but do you know what, my students are trying. I've listened to their stories… The challenges they face to get to class are overwhelming". My Careers Advisor friend nodded in agreement, telling us similar stories from her own students and the role she plays in ensuring this gap between High School and University is bridged. It was then my turn to share my work stories, and when I did, it surprised us all that while we are at different stages of the Education system, we all shared the same challenges. If the issue is not properly addressed in the early years, it continues into high school and eventually into university. Alternatively, young people are excluded from school which is detrimental to their chances at a good life, however this is defined. So, what exactly is happening at my end of the spectrum? Young Sione was referred to TYMS last year by his school because he was at high risk of exclusion. The reasons noted in his referral included: a lack of focus, impulsivity, causing class disruption, easily angered, absconding, and poor academic achievement. Sione is a 15-year-old male of Samoan, Maori, and European descent. Sione lives with his single mother Jane and younger brother Tui. Sione’s grandfather passed away when he was 3 years old, and his loss deeply affected Sione as his papa was his only friend and father-figure. Jane also struggled with her father’s loss, especially as he was her ‘rock’ - her main source of stability both financially and emotionally. With her father gone, Jane was forced to restart on her own. For 10 years they moved from home to home, whatever was affordable with the income she received from her benefit. Sione’s father was not in the picture, so there was no source of parental support from him financially and emotionally to assist with Sione's care. When I spoke with Jane, she acknowledged with sadness the impact their constant moving had on Sione - his education was disrupted, he was unable to make long-term friends, and the neighbourhoods they lived in were no place to raise a young child. “But what else can you do when rent is expensive, and when all the bills are paid you are left with an average of $40 per week to allocate to food and other expenses?”, Jane said. “I always prayed that my son didn't get sick because if he did, I wouldn't know how to give him the healthcare he would need”. Jane also admitted to the many times she would change the name on her power bill just to get by. She also humorously referred to herself as a ‘regular’ at WINZ and Housing NZ. For Jane, the main priority at the time was to get a Housing NZ home for her and Sione so that Sione could go to one school and make friends. But Sione was also growing up quickly, and while she was fighting to survive, her son was slowly falling through the cracks. He was disengaged from school and from her. His teachers identified him as a ‘problem student’. And the police often dropped him home after midnight. When Jane finally found a Housing NZ home, she said “it was already too late, my son was too far gone into the deep end hanging with the wrong crowds and getting into trouble”. Jane was tearful as she recounted the day she got the call from Housing NZ that they had a home for her. She was sitting at the WINZ reception waiting for another appointment. While she waited, she contemplated the possibility of giving her sons to CYFS care (Tui was 1 year old at the time). In her mind, she had done everything she could but despite all her efforts, her sons were suffering. She did not want that life for them. Perhaps the system could provide her sons with the good life she was unable to provide. Fortunately for Jane, the call and solution to some of her problems had arrived on time, and she moved with into their new home with her sons within a week. For Sione on the other hand, his performance at school had deteriorated, which resulted in his involvement with TYMS. With the help of his TYMS Mentor and TYMS Family Advocate, Sione remained in school and is still there to this day. Our TYMS team worked with Sione and his mother, building Sione's executive function skills, addressing the risk factors in his environment, and adding the protective factors necessary to strengthen his resilience. In my conversation with Jane, she expressed immense gratitude for TYMS help with her son, especially his Sai Bhai mentor who, “never gave up" on Sione. Seeing her son’s positive progress every time he returned home from his day with his mentor also empowered Jane to do better for herself and her sons. Jane is now in her last semester of her university degree. We have all encountered Sione’s in our lives, except the only things we are often told about these Sione’s are the statistics and stereotypes associated with the language he is labelled by: 'problem student’ or ‘at-risk teen’. We are rarely told Sione’s story. We are also not told that young people like Sione who experience four or more risk factors in their lives are highly vulnerable and at high risk of experiencing toxic stress. Toxic stress, amongst its other negative impacts, robs young people of their executive function skills, the very skills that are crucial to young people's academic and social success. We continue to work with many young Sione’s on an individual basis and in groups. We have an in-school healthy relationships group mentoring programme that directly addresses MOE’s goal of 'keeping at-risk youth in mainstream classes'. This 8-week program is currently running in various primary schools across West Auckland, with schools out South Auckland on the waiting list for next term. We also run an education and pastoral care program in a Youth Justice Residential Home for young on remand. Both programs are gaining nation-wide attention for the positive outcomes experienced by our young people, their whānau, and schools. What have we learned? Combining the insights from my two friends work experiences with our TYMS learnings from over 5 years of working with young people who are at-risk of being excluded, or are already excluded from schools, we understand the following:

When our young people and their whānau come to TYMS, we first exchange stories to foster the trust and empathy that is needed to establish the relationships that enable us to do the work we do successfully. When we listen to young people's stories, they cease to become ‘just another number’ or ‘another statistic’; instead, they become our child, our young person, our whānau, our neighbour, our people.

Regardless of our job descriptions and where we are in our careers, as adults, we each have a role in the wellbeing and future success of our young people. 'A manuia fanau, e manuia aiga, nuu, Ekalesia, ma le atunuu - When our children are successful, our families, villages, churches, and nation all prosper'. It takes a village to raise a child. * Jane and Sione have kindly given their permission for us to tell their story.

0 Comments

Author: Koleta Savaii Physical well-being is central to the fulfillment of our everyday tasks and long-term goals. We need to be in good physical health to be able to go to school or work and to participate in activities with our families and friends. In turn, we feel good about ourselves, we find enjoyment in what we do, and this has spill-over effects to other areas of our lives. It benefits society.

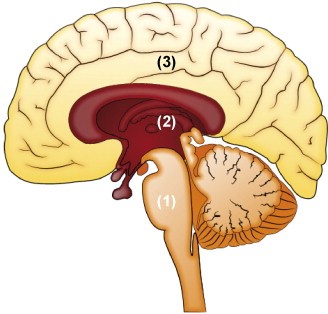

Improving the physical well-being of the young people who come to TYMS is a major goal of our service. We accomplish this through our focus on these two areas: the executive function and social cognition. The executive function and social cognition are associated with the prefrontal cortex which is situated in the frontal lobe part of the brain. The executive function is used to describe the capacity that allows us to control and coordinate our thoughts and behaviours. These skills include selective attention, decision-making, voluntary response inhibition, and working memory. Social cognition focuses on how people process, store, and apply information about other people and social situations. The way we think about others plays a major role in how we think, feel, and interact with the world around us. Puberty, which is associated with adolescence, represents a period of synaptic reorganisation in the brain (think of electrical wires in your computer reorganising themselves). Consequently, the brain might be more sensitive to experiential input at this period of time in the realm of executive function and social cognition. What this means is that, the adolescent brain is at a pruning stage which makes it an excellent time to foster executive function and social cognitive skills, which can last into adulthood. So, where does physical wellbeing come in? Physical activity requires volition, planning, purposive action, performance monitoring, and inhibition – skills associated with the executive function. To successfully adopt or change physical activity behaviour, an individual must form a conscious intention about what activity they wish to adopt (volition), identify the sequence of actions required to achieve the intended activity (planning), initiate and maintain focus on the chosen activity over time (purposive action), compare actual progress with planned progress over time, identify and correct mistakes (performance monitoring), and overcome the temptation to remain inactive or eat an unhealthy diet (inhibition). These are the stages our young people go through when we work with them on improving their physical well-being. The great thing about these skills is that they are transferable to other areas of life where planning, decision making, etc. are needed… like Maths. Research shows that kids who engage in physical activity significantly improve in Maths compared to kids who don’t. To improve social cognition, the literature suggests that accumulating social experiences is crucial for social cognitive processes. While we have a gym on site where young people carry out their exercise regimes, our mentors also spice things up by taking the young people out to parks, swimming pools, and local sports clubs. Given that majority of the young people who come to TYMS face social exclusion in one form or another, taking them out to the community aids in re-establishing their social connections, minimising their experiences of exclusion. When we are surrounded by lots of people, it is a learning ground for our social cognitive processes. We know anger, happiness, fear and joy because we see these emotions expressed on other’s faces or in their behaviour. And we know the boundaries to our own expressions of these emotions because others act as guides, expressing approval or disapproval when we behave or act in certain ways. Social connection fosters emotional intelligence and empathy, which are essential characteristics to being a good member of society. Here at TYMS, our approach to improving our young people’s physical well-being is holistic. It is about good physical health on top of fostering executive function and social cognition skills. These skills combined will enable our young people to reach their full potentials and secure positive futures. Author: Koleta Savaii  Every parent wants their child to do well in school. We all know that a good education is the key to a wide range of opportunities that ultimately lead to a “good life”. Now, people have their own ideas about what this good life entails. But we can all agree that it is one which is free from hunger, poverty, homelessness, fear of crime, and ill-health. Academic wellbeing encompasses young people’s attainment of knowledge, skills, concepts, and strategies that enables them to succeed in school, and eventually to deal with the increasingly complex worlds of family life, work, and citizenship. There is considerable research that has been carried out globally to identify pathways to achieving academic well-being. These include improvements in school curriculum, young people’s diets, their home environment, teacher behaviour, community participation, and the removal of toxic stress. While valuable, this data is by no means the full story, especially if we want to understand the ways in which we can improve young Pacific people’s academic well-being. Pacific students are not doing so well in New Zealand schools. The data also shows that Pacific females are doing much better in secondary through to tertiary education than their male counterparts. To make sense of these findings, Professor Tagaloatele Fairbairn-Dunlop argued that we need to review educational outcomes through a Pacific gender lens, so that we can identify how cultural expectations might influence the school experience today. So, what is this “Pacific gender lens”? To explain, I’ll reflect on my own journey. I am a Samoan female. I was born in New Zealand, but I spent majority of my childhood and teenage years in Samoa. I was raised by grandparents, uncles, aunts, church family, and village – yes it does take a village to raise a child. My grandfather was my idol. He taught me how to read using the Samoan Bible. He said reading the newspaper was a waste of time, all the knowledge I seek is in the Bible. He taught me how to write my name... I have never come across anyone so patient. He taught me basic maths: ‘I am giving you a dollar, go to the shop and buy me a .50cent razor blade, how much change should you come back with?’ But my favourite memories of him were the nights where he would tell me a fagogo (a Samoan form of storytelling). Through his fagogo I learned about my family genealogy, the markers of our family lands, the origin of our matai (chief) title and its meaning, and my responsibilities as a Samoan female. I wanted to be just like him. I wanted to speak the language of the matai. I wanted to be a skilled orator. I used to follow him to village meetings and listen to the matai debate village issues. The majority of the matai in these village meetings were men. Even the boys my age had business in the meeting house. I hated that I wasn’t a boy. Girls don’t do matai stuff, or so I thought. ‘Focus on your education, my child. If you succeed in school, you can have anything you want in this life’, my grandfather said. And that’s how I ended up in a New Zealand University; although I still envy my male cousins who seem to know how to do everything. This is the gendered division of roles and responsibilities in thefa’aSamoa that Professor Fairbairn-Dunlop and many Samoan scholars write about. Unlike the Western division of labour where women are subordinate to men, Samoan men and women have complementary roles. In traditional times, men were responsible for political authority, defence and warfare and the production of food and women were responsible for moral authority, ceremony and hospitality, and the production of exchange valuables such as the ie toga (fine mats). For the maintenance of society’s well-being, everyone was expected to behave according to their ascribed place. While these ideological divisions were held, actual roles might be modified according to need, opportunity, and the desire to maintain the family good. In applying this Samoan gender lens to the New Zealand educational data, Professor Fairbairn-Dunlop found that the Samoan male norm which discourages failure hindered boys’ full participation in academia. his was one reason why the majority of Samoan males were drawn to non-academic avenues such as sports, to retain their prestige. While females were using the opportunities education offered to learn new skills and knowledge, their participation in the public domain still remained minimal. Like Samoa, many Pacific cultural systems are influenced by gender and a consideration for factors such as age, family status and place. These inform Pacific peoples roles, responsibilities, behaviours and expectations. The academic wellbeing of Pacific youth is contingent on our understanding and recognition of the influences of these cultural systems, in addition to improvements in other areas affecting young people’s education including school curriculums, nutrition, the home environment, and communities. Author: Koleta Savaii  “Who am I?” is a question that we have no doubt asked of ourselves at some point during the course of our lives. But perhaps the stage at which this question becomes a preoccupation is during our adolescent years. Our teenage years are a complex time; we undergo tremendous transformations physiologically (e.g. puberty), psychologically (e.g. advent of formal operational thinking), and socially (e.g. acceptance of adult responsibilities), all embedded within larger social, cultural, and historical contexts and forces. For many Pacific peoples, the answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ is reflected in this quote by the Head of States of Samoa, Susuga Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Efi: "I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a tofi (inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging." As captured in this quote, Pacific peoples view the self as comprised of their social relationships, their land and physical resources, and the spiritual. This view of the self and the relationship between the self and others features the person not as separate from the social and environmental context, but as more connected and less differentiated from them. The emphasis is on attending to them, fitting in, and harmonious interdependence with them. Hence, the Pacific self cannot be viewed independent of Pacific culture. As envisioned by the Fonofale model, the Pacific self as a Samoan fale envisages Pacific culture as the roof. Culture represents ethnic-specific Pacific values and beliefs as the overarching or holistic philosophy of life. The roof is traditionally thatched with sugarcane leaves and when properly prepared and attached the first time, it will last approximately 10-15 years. The cone shaped roof allows rain to easily fall to the ground without moisture permeating the leaves and causing leaks inside. Of course, during sunny days the high dome allows the heat to rise and seep through the thatching, cooling the house. Today, however, most roofs are made of imported materials (i.e. timber, nails, and corrugated roofing iron) but the fundamentals remain the same. Samoa has a well-known saying ‘e sui faiga ae tumau fa’avae’ – ‘practices may change but the foundations remain’. Likewise, our ethnic-specific Pacific cultures are constantly evolving and adapting to the changing times, but the fundamentals remain. These include: reciprocity, respect, genealogy, tapu relationships, language of respect, and belonging:

For our Pacific youth in New Zealand, their cultures may consist of these Pacific concepts, plus elements from other cultures they are exposed to at school, in their communities, and on the Internet. Establishing and securing an identity is no doubt a challenging task, but our youth are faring well regardless. There is also a general interest among our young people to learn more about their ethnic-specific Pacific customs and traditions, as evident in the needs of the young people who come to TYMS. It is well established that when young people develop a strong sense of who they are and where they are headed, they are more likely to engage in successful adult roles and mature interpersonal relationships. Consequently, when they are unclear about who they are, they are highly likely to engage in destructive behaviour, experience distress, and have difficulties maintaining healthy relationships with others. “In the social jungle of human existence there is no feeling of being alive without a sense of identity” (Erik Erikson) At TYMS we believe in the value of knowing and having a firm sense of one’s identity and cultural heritage to achieving overall wellbeing. But we also recognise the changing times and contexts in which our young people live today. Cultural identity is central to our program, which we address in our academic mentoring programs and incorporate in our everyday practices.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2018

|

What Our Clients Are Saying

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed