|

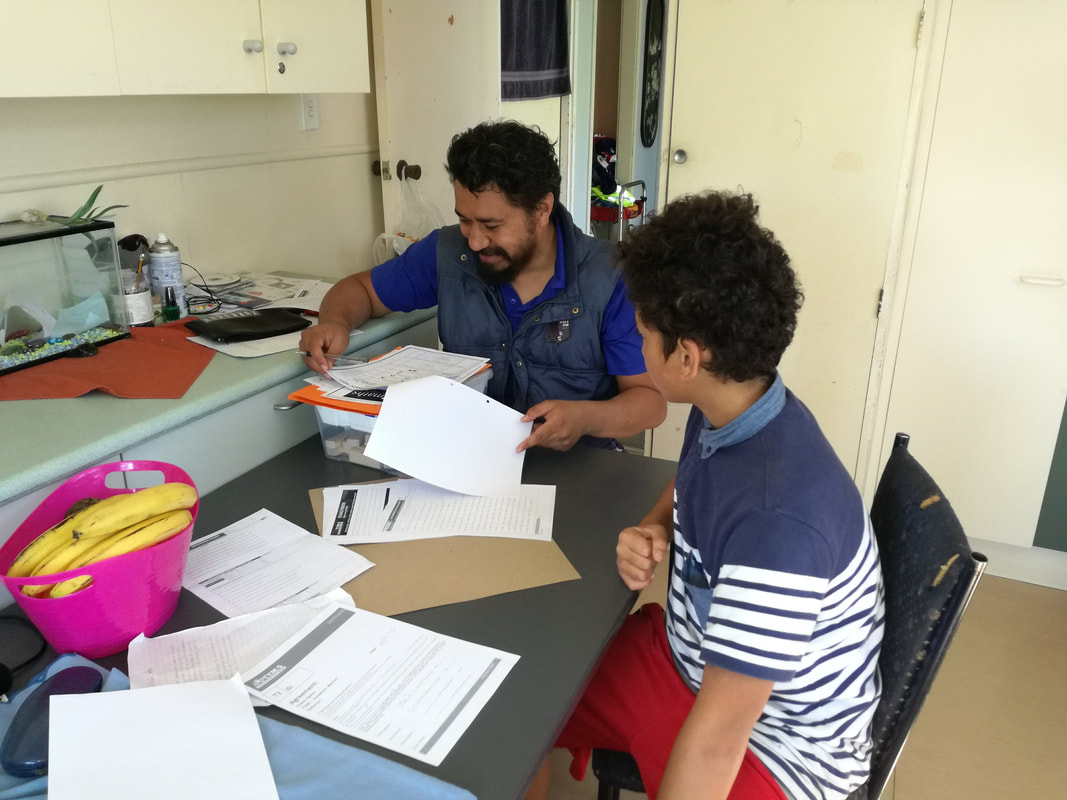

Author: Koleta Savaii  Every parent wants their child to do well in school. We all know that a good education is the key to a wide range of opportunities that ultimately lead to a “good life”. Now, people have their own ideas about what this good life entails. But we can all agree that it is one which is free from hunger, poverty, homelessness, fear of crime, and ill-health. Academic wellbeing encompasses young people’s attainment of knowledge, skills, concepts, and strategies that enables them to succeed in school, and eventually to deal with the increasingly complex worlds of family life, work, and citizenship. There is considerable research that has been carried out globally to identify pathways to achieving academic well-being. These include improvements in school curriculum, young people’s diets, their home environment, teacher behaviour, community participation, and the removal of toxic stress. While valuable, this data is by no means the full story, especially if we want to understand the ways in which we can improve young Pacific people’s academic well-being. Pacific students are not doing so well in New Zealand schools. The data also shows that Pacific females are doing much better in secondary through to tertiary education than their male counterparts. To make sense of these findings, Professor Tagaloatele Fairbairn-Dunlop argued that we need to review educational outcomes through a Pacific gender lens, so that we can identify how cultural expectations might influence the school experience today. So, what is this “Pacific gender lens”? To explain, I’ll reflect on my own journey. I am a Samoan female. I was born in New Zealand, but I spent majority of my childhood and teenage years in Samoa. I was raised by grandparents, uncles, aunts, church family, and village – yes it does take a village to raise a child. My grandfather was my idol. He taught me how to read using the Samoan Bible. He said reading the newspaper was a waste of time, all the knowledge I seek is in the Bible. He taught me how to write my name... I have never come across anyone so patient. He taught me basic maths: ‘I am giving you a dollar, go to the shop and buy me a .50cent razor blade, how much change should you come back with?’ But my favourite memories of him were the nights where he would tell me a fagogo (a Samoan form of storytelling). Through his fagogo I learned about my family genealogy, the markers of our family lands, the origin of our matai (chief) title and its meaning, and my responsibilities as a Samoan female. I wanted to be just like him. I wanted to speak the language of the matai. I wanted to be a skilled orator. I used to follow him to village meetings and listen to the matai debate village issues. The majority of the matai in these village meetings were men. Even the boys my age had business in the meeting house. I hated that I wasn’t a boy. Girls don’t do matai stuff, or so I thought. ‘Focus on your education, my child. If you succeed in school, you can have anything you want in this life’, my grandfather said. And that’s how I ended up in a New Zealand University; although I still envy my male cousins who seem to know how to do everything. This is the gendered division of roles and responsibilities in thefa’aSamoa that Professor Fairbairn-Dunlop and many Samoan scholars write about. Unlike the Western division of labour where women are subordinate to men, Samoan men and women have complementary roles. In traditional times, men were responsible for political authority, defence and warfare and the production of food and women were responsible for moral authority, ceremony and hospitality, and the production of exchange valuables such as the ie toga (fine mats). For the maintenance of society’s well-being, everyone was expected to behave according to their ascribed place. While these ideological divisions were held, actual roles might be modified according to need, opportunity, and the desire to maintain the family good. In applying this Samoan gender lens to the New Zealand educational data, Professor Fairbairn-Dunlop found that the Samoan male norm which discourages failure hindered boys’ full participation in academia. his was one reason why the majority of Samoan males were drawn to non-academic avenues such as sports, to retain their prestige. While females were using the opportunities education offered to learn new skills and knowledge, their participation in the public domain still remained minimal. Like Samoa, many Pacific cultural systems are influenced by gender and a consideration for factors such as age, family status and place. These inform Pacific peoples roles, responsibilities, behaviours and expectations. The academic wellbeing of Pacific youth is contingent on our understanding and recognition of the influences of these cultural systems, in addition to improvements in other areas affecting young people’s education including school curriculums, nutrition, the home environment, and communities.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2018

|

What Our Clients Are Saying

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed