|

Author: Koleta Savaii In the media last week, MOE released its review of the Alternative Education sector. In a nutshell, the review concluded that the alternative education has been “largely ineffective”, with suggestions for “a stronger move to help schools keep the most at-risk teens in mainstream classes”.

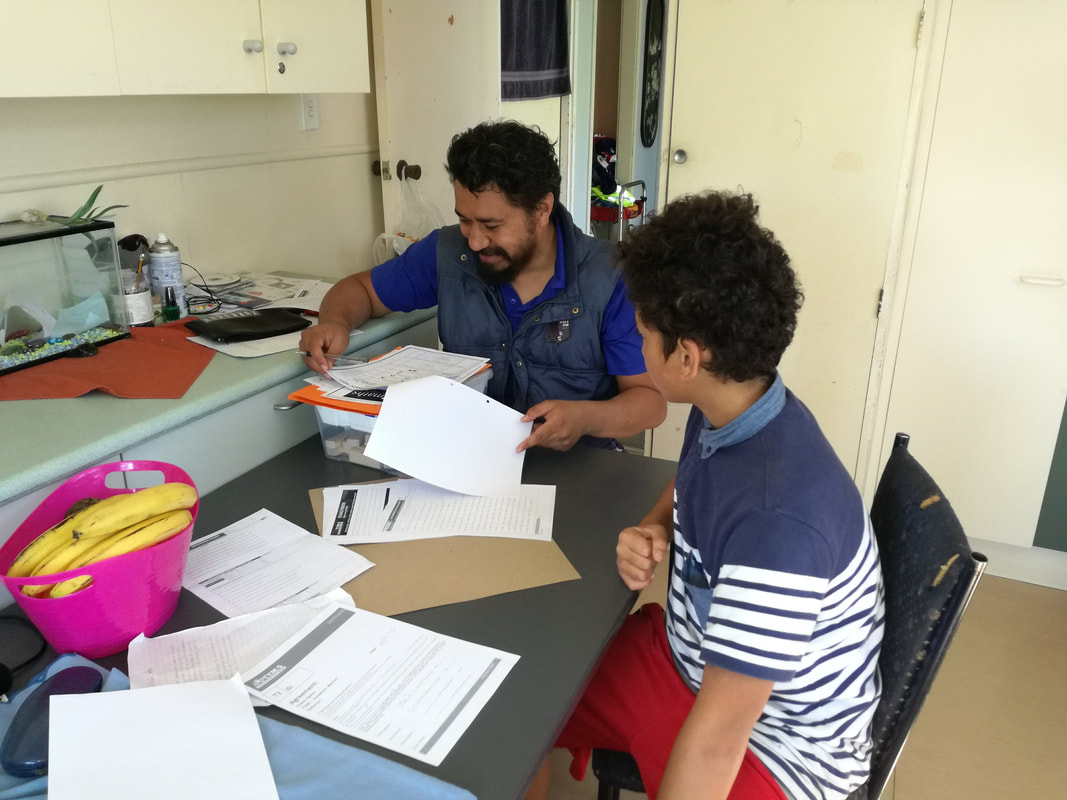

‘Keeping at-risk young people in school' is exactly what TYMS have been doing since its inception, and we have seen tremendous successes. The results of our 2016 Evaluations Outcomes Harvest revealed that of our total 183 clients, 73% remained in school, 9% returned to school after being excluded, and 2% transitioned into Alternative Education. While we are pleased with these results, our insights and key learnings over the many years of working with our young people and their whānau have taught us that the suggestion to ‘keep at risk youth in mainstream classes’ is not as simple as it sounds for all involved. I had the privilege of catching up with two of my close friends from my undergrad and postgrad tutoring years last Saturday for brunch. Since our tutoring years, one friend is now an Academic and Careers advisor at a South Auckland high school, and the other is a lecturer in one of the University's Certificate Programmes. We reminisced about our tutoring days and the challenges we faced, especially with students who were ill-prepared for university. My lecturer friend told us that not much has changed, "but do you know what, my students are trying. I've listened to their stories… The challenges they face to get to class are overwhelming". My Careers Advisor friend nodded in agreement, telling us similar stories from her own students and the role she plays in ensuring this gap between High School and University is bridged. It was then my turn to share my work stories, and when I did, it surprised us all that while we are at different stages of the Education system, we all shared the same challenges. If the issue is not properly addressed in the early years, it continues into high school and eventually into university. Alternatively, young people are excluded from school which is detrimental to their chances at a good life, however this is defined. So, what exactly is happening at my end of the spectrum? Young Sione was referred to TYMS last year by his school because he was at high risk of exclusion. The reasons noted in his referral included: a lack of focus, impulsivity, causing class disruption, easily angered, absconding, and poor academic achievement. Sione is a 15-year-old male of Samoan, Maori, and European descent. Sione lives with his single mother Jane and younger brother Tui. Sione’s grandfather passed away when he was 3 years old, and his loss deeply affected Sione as his papa was his only friend and father-figure. Jane also struggled with her father’s loss, especially as he was her ‘rock’ - her main source of stability both financially and emotionally. With her father gone, Jane was forced to restart on her own. For 10 years they moved from home to home, whatever was affordable with the income she received from her benefit. Sione’s father was not in the picture, so there was no source of parental support from him financially and emotionally to assist with Sione's care. When I spoke with Jane, she acknowledged with sadness the impact their constant moving had on Sione - his education was disrupted, he was unable to make long-term friends, and the neighbourhoods they lived in were no place to raise a young child. “But what else can you do when rent is expensive, and when all the bills are paid you are left with an average of $40 per week to allocate to food and other expenses?”, Jane said. “I always prayed that my son didn't get sick because if he did, I wouldn't know how to give him the healthcare he would need”. Jane also admitted to the many times she would change the name on her power bill just to get by. She also humorously referred to herself as a ‘regular’ at WINZ and Housing NZ. For Jane, the main priority at the time was to get a Housing NZ home for her and Sione so that Sione could go to one school and make friends. But Sione was also growing up quickly, and while she was fighting to survive, her son was slowly falling through the cracks. He was disengaged from school and from her. His teachers identified him as a ‘problem student’. And the police often dropped him home after midnight. When Jane finally found a Housing NZ home, she said “it was already too late, my son was too far gone into the deep end hanging with the wrong crowds and getting into trouble”. Jane was tearful as she recounted the day she got the call from Housing NZ that they had a home for her. She was sitting at the WINZ reception waiting for another appointment. While she waited, she contemplated the possibility of giving her sons to CYFS care (Tui was 1 year old at the time). In her mind, she had done everything she could but despite all her efforts, her sons were suffering. She did not want that life for them. Perhaps the system could provide her sons with the good life she was unable to provide. Fortunately for Jane, the call and solution to some of her problems had arrived on time, and she moved with into their new home with her sons within a week. For Sione on the other hand, his performance at school had deteriorated, which resulted in his involvement with TYMS. With the help of his TYMS Mentor and TYMS Family Advocate, Sione remained in school and is still there to this day. Our TYMS team worked with Sione and his mother, building Sione's executive function skills, addressing the risk factors in his environment, and adding the protective factors necessary to strengthen his resilience. In my conversation with Jane, she expressed immense gratitude for TYMS help with her son, especially his Sai Bhai mentor who, “never gave up" on Sione. Seeing her son’s positive progress every time he returned home from his day with his mentor also empowered Jane to do better for herself and her sons. Jane is now in her last semester of her university degree. We have all encountered Sione’s in our lives, except the only things we are often told about these Sione’s are the statistics and stereotypes associated with the language he is labelled by: 'problem student’ or ‘at-risk teen’. We are rarely told Sione’s story. We are also not told that young people like Sione who experience four or more risk factors in their lives are highly vulnerable and at high risk of experiencing toxic stress. Toxic stress, amongst its other negative impacts, robs young people of their executive function skills, the very skills that are crucial to young people's academic and social success. We continue to work with many young Sione’s on an individual basis and in groups. We have an in-school healthy relationships group mentoring programme that directly addresses MOE’s goal of 'keeping at-risk youth in mainstream classes'. This 8-week program is currently running in various primary schools across West Auckland, with schools out South Auckland on the waiting list for next term. We also run an education and pastoral care program in a Youth Justice Residential Home for young on remand. Both programs are gaining nation-wide attention for the positive outcomes experienced by our young people, their whānau, and schools. What have we learned? Combining the insights from my two friends work experiences with our TYMS learnings from over 5 years of working with young people who are at-risk of being excluded, or are already excluded from schools, we understand the following:

When our young people and their whānau come to TYMS, we first exchange stories to foster the trust and empathy that is needed to establish the relationships that enable us to do the work we do successfully. When we listen to young people's stories, they cease to become ‘just another number’ or ‘another statistic’; instead, they become our child, our young person, our whānau, our neighbour, our people.

Regardless of our job descriptions and where we are in our careers, as adults, we each have a role in the wellbeing and future success of our young people. 'A manuia fanau, e manuia aiga, nuu, Ekalesia, ma le atunuu - When our children are successful, our families, villages, churches, and nation all prosper'. It takes a village to raise a child. * Jane and Sione have kindly given their permission for us to tell their story.

0 Comments

Author: Koleta Savaii  Every parent wants their child to do well in school. We all know that a good education is the key to a wide range of opportunities that ultimately lead to a “good life”. Now, people have their own ideas about what this good life entails. But we can all agree that it is one which is free from hunger, poverty, homelessness, fear of crime, and ill-health. Academic wellbeing encompasses young people’s attainment of knowledge, skills, concepts, and strategies that enables them to succeed in school, and eventually to deal with the increasingly complex worlds of family life, work, and citizenship. There is considerable research that has been carried out globally to identify pathways to achieving academic well-being. These include improvements in school curriculum, young people’s diets, their home environment, teacher behaviour, community participation, and the removal of toxic stress. While valuable, this data is by no means the full story, especially if we want to understand the ways in which we can improve young Pacific people’s academic well-being. Pacific students are not doing so well in New Zealand schools. The data also shows that Pacific females are doing much better in secondary through to tertiary education than their male counterparts. To make sense of these findings, Professor Tagaloatele Fairbairn-Dunlop argued that we need to review educational outcomes through a Pacific gender lens, so that we can identify how cultural expectations might influence the school experience today. So, what is this “Pacific gender lens”? To explain, I’ll reflect on my own journey. I am a Samoan female. I was born in New Zealand, but I spent majority of my childhood and teenage years in Samoa. I was raised by grandparents, uncles, aunts, church family, and village – yes it does take a village to raise a child. My grandfather was my idol. He taught me how to read using the Samoan Bible. He said reading the newspaper was a waste of time, all the knowledge I seek is in the Bible. He taught me how to write my name... I have never come across anyone so patient. He taught me basic maths: ‘I am giving you a dollar, go to the shop and buy me a .50cent razor blade, how much change should you come back with?’ But my favourite memories of him were the nights where he would tell me a fagogo (a Samoan form of storytelling). Through his fagogo I learned about my family genealogy, the markers of our family lands, the origin of our matai (chief) title and its meaning, and my responsibilities as a Samoan female. I wanted to be just like him. I wanted to speak the language of the matai. I wanted to be a skilled orator. I used to follow him to village meetings and listen to the matai debate village issues. The majority of the matai in these village meetings were men. Even the boys my age had business in the meeting house. I hated that I wasn’t a boy. Girls don’t do matai stuff, or so I thought. ‘Focus on your education, my child. If you succeed in school, you can have anything you want in this life’, my grandfather said. And that’s how I ended up in a New Zealand University; although I still envy my male cousins who seem to know how to do everything. This is the gendered division of roles and responsibilities in thefa’aSamoa that Professor Fairbairn-Dunlop and many Samoan scholars write about. Unlike the Western division of labour where women are subordinate to men, Samoan men and women have complementary roles. In traditional times, men were responsible for political authority, defence and warfare and the production of food and women were responsible for moral authority, ceremony and hospitality, and the production of exchange valuables such as the ie toga (fine mats). For the maintenance of society’s well-being, everyone was expected to behave according to their ascribed place. While these ideological divisions were held, actual roles might be modified according to need, opportunity, and the desire to maintain the family good. In applying this Samoan gender lens to the New Zealand educational data, Professor Fairbairn-Dunlop found that the Samoan male norm which discourages failure hindered boys’ full participation in academia. his was one reason why the majority of Samoan males were drawn to non-academic avenues such as sports, to retain their prestige. While females were using the opportunities education offered to learn new skills and knowledge, their participation in the public domain still remained minimal. Like Samoa, many Pacific cultural systems are influenced by gender and a consideration for factors such as age, family status and place. These inform Pacific peoples roles, responsibilities, behaviours and expectations. The academic wellbeing of Pacific youth is contingent on our understanding and recognition of the influences of these cultural systems, in addition to improvements in other areas affecting young people’s education including school curriculums, nutrition, the home environment, and communities. Author: Koleta Savaii Adolescents are at a transitional stage – from their high dependence on parents and family to a need for autonomy and independence as they progress to adulthood.

While at this stage the role of the family in the adolescent’s life is secondary to that of the peer group, a close best friend, or a romantic partner, this does not mean family support is no longer needed. Adolescent researchers have established that different types of relationships fulfill specific interpersonal needs. For example, in romantic relationships, adolescents learn the social aspects of this type of relationship from their relationships with their parents and close friends (i.e., intimacy, conflict resolution, trust, empathy, and compassion), while the sexual aspects are learned from a dating partner. For healthy youth and consequently healthy adults, we need to ensure that every one of their relationships are healthy, and that they provide positive learning experiences. The adolescent years are also critical to the formation of one’s identity. At any point in history we will find that the opportunities available to youth for identity formation differ. For instance, for the grandparents of today’s youth, cultural exploration was restricted by geographical boundaries and the only cultures available was that of their families, church and communities. With increasing globalisation and the popularity of social media, today’s youth literally have access to thousands of cultures and opportunities for identification at their fingertips. A multitude of options to choose from can be distressing for any individual. But this can be especially stressful for adolescents whose brain areas that are responsible for executive function tasks (i.e. self-control, decision making) are not yet fully mature. This region of the brain is also responsible for a variety of other functions, its a common reservoir. Therefore, when we exercise self-control, we tax this common reservoir. For example, trying to maintain a healthy weight by exercising regularly and eating a healthy diet, while at the same time controlling the urge to eat unhealthy foods and stay in bed all day is physically taxing on this common reservoir. If it is not replenished (i.e. through positive self-affirmations, glucose consumption), then we are unable to exercise self-control in other areas of our lives (e.g. we procrastinate in our school work, or we over-spend beyond our available finances). Executive function is like a fuel tank that needs to stay filled. Positive self affirmation is one way of filling up our executive function tank. Adolescents are therefore at a stage in their lives where they need all the support they can get to keep them on track. Unfortunately, the availability of adults or other individuals willing to provide help and/or show interest in their problems is very limited. And this seems unfortunate, when an overview of the literature in this area shows clear links between the quality of adolescents’ supportive relationships with such features as self-esteem, suicidal and delinquent behaviours, emotional illness, and negative emotional states. The availability of positive social support is important, but this has to be accessible and of value to the individual. For example, in many Pacific families, gaining an education is highly valued. Generations of Pacific families have left their homelands for this very reason. For many Pacific parents, their motto is “Education is the key to a good life”. They wish for their children a life that they couldn’t experience themselves while growing up, so they push for their children to gain an education so that they can get good jobs to have a chance at the good life. Hence, adults in the community that provide mentoring and academic support is valuable to both Pacific youth and their families. Social support provided by parents and peers is crucial to the health and wellbeing of young people. This resource will not be utilised, however, if the barriers around access are not addressed. Barriers can include individual personality factors (e.g. low self-esteem), culture (e.g. cultural norms/attitudes around help-seeking), and financial (e.g. transportation costs). The availability of a valued resource coupled with the removal of barriers to accessing such resource, is key to ensuring young people are making use of the programs available to them within schools and in their communities. Social support whether it be provided by peers, parents, and members of the community is crucial to the health and wellbeing of young people. Positive adults who show an interest in youth and their problems is sometimes all it takes to keep a young person outside of prison, off the streets, and in school. Author: Koleta Savaii  “Who am I?” is a question that we have no doubt asked of ourselves at some point during the course of our lives. But perhaps the stage at which this question becomes a preoccupation is during our adolescent years. Our teenage years are a complex time; we undergo tremendous transformations physiologically (e.g. puberty), psychologically (e.g. advent of formal operational thinking), and socially (e.g. acceptance of adult responsibilities), all embedded within larger social, cultural, and historical contexts and forces. For many Pacific peoples, the answer to the question ‘Who am I?’ is reflected in this quote by the Head of States of Samoa, Susuga Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Efi: "I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a tofi (inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging." As captured in this quote, Pacific peoples view the self as comprised of their social relationships, their land and physical resources, and the spiritual. This view of the self and the relationship between the self and others features the person not as separate from the social and environmental context, but as more connected and less differentiated from them. The emphasis is on attending to them, fitting in, and harmonious interdependence with them. Hence, the Pacific self cannot be viewed independent of Pacific culture. As envisioned by the Fonofale model, the Pacific self as a Samoan fale envisages Pacific culture as the roof. Culture represents ethnic-specific Pacific values and beliefs as the overarching or holistic philosophy of life. The roof is traditionally thatched with sugarcane leaves and when properly prepared and attached the first time, it will last approximately 10-15 years. The cone shaped roof allows rain to easily fall to the ground without moisture permeating the leaves and causing leaks inside. Of course, during sunny days the high dome allows the heat to rise and seep through the thatching, cooling the house. Today, however, most roofs are made of imported materials (i.e. timber, nails, and corrugated roofing iron) but the fundamentals remain the same. Samoa has a well-known saying ‘e sui faiga ae tumau fa’avae’ – ‘practices may change but the foundations remain’. Likewise, our ethnic-specific Pacific cultures are constantly evolving and adapting to the changing times, but the fundamentals remain. These include: reciprocity, respect, genealogy, tapu relationships, language of respect, and belonging:

For our Pacific youth in New Zealand, their cultures may consist of these Pacific concepts, plus elements from other cultures they are exposed to at school, in their communities, and on the Internet. Establishing and securing an identity is no doubt a challenging task, but our youth are faring well regardless. There is also a general interest among our young people to learn more about their ethnic-specific Pacific customs and traditions, as evident in the needs of the young people who come to TYMS. It is well established that when young people develop a strong sense of who they are and where they are headed, they are more likely to engage in successful adult roles and mature interpersonal relationships. Consequently, when they are unclear about who they are, they are highly likely to engage in destructive behaviour, experience distress, and have difficulties maintaining healthy relationships with others. “In the social jungle of human existence there is no feeling of being alive without a sense of identity” (Erik Erikson) At TYMS we believe in the value of knowing and having a firm sense of one’s identity and cultural heritage to achieving overall wellbeing. But we also recognise the changing times and contexts in which our young people live today. Cultural identity is central to our program, which we address in our academic mentoring programs and incorporate in our everyday practices. Author: Koleta Savaii The family is the most important institution in children’s lives.

For many of our Pacific children, the family is where language, values, and cultural and religious beliefs are taught and nurtured. A strong family is one where members can depend on each other, where people are treated well, where values are shared and respected and where there is financial security. Just like a well-built fale, a strong family can weather even the greatest storm. Sadly, not all our Pacific families are weathering the storm. A shift in New Zealand’s socio-economic environment has contributed to Pacific communities suffering from cultural erosion, social fragmentation and an increasing loss of identity. This has instigated changes in Pacific family structures and dynamics, including increases in de facto relationships, shifts towards single parenting, and changes in traditional attitudes towards care for the elderly and the young. These changes have undermined our family units and the ways in which family members relate to each other. Many Pacific families are underpinned by cultural values of fa’aaloalo (respect), va fealoao’i (relational boundaries), tautua (service), and alofa (love). When these values are lost, the family can become a place of suffering and dysfunction, rather than sites that nurture strong and vibrant families. When children and young people have strong and healthy relationships with their families, their health and wellbeing increases and they are less likely to be involved in delinquent behaviours. Children are believed to be a tofi (inheritance) from God. The Christian bible teaches us to ‘Train up a child in the way he should go; and when he is old, he will not depart from it’ -Proverbs 22:6. Samoa also has a well-known saying “O le tama a le tagata e fafaga i upu ma tala, a o le tama a le manu e fafaga i fuga o laau” – The offspring of men are fed with words but the offspring of birds are fed with seeds. In the EFKS (Congregational Christian Church of Samoa) tradition, when a child is baptised, all who witness this sacred ceremony (the family and the church community) are endowed with the responsibility of raising the baptised child in the ways of the church and fa’aSamoa (Samoan way of life). Hence the saying: ‘It takes a village to raise a child’. Pacific peoples have a holistic view of the world. This worldview is comprised of the social (people), the physical (land and resources), and thespiritual (God the creator), where individual and collective wellbeing is a consequence of a balance and harmony between these interrelated domains. This holistic worldview is encapsulated in the well-known Fonofale model of Pacific health and wellbeing. According to the Fonofale model, the Pacific self is envisioned as a fale (a Samoan house;right). The fa’avae (foundation) is central to the Samoan fale; a solid foundation ensures the fale will withstand any changes in the weather. Likewise, Pacific wellbeing as envisioned by the Fonofale model, requires a strong, healthy and vibrant family. It is well-established that when children and young people have strong and healthy relationships with their families, their health and wellbeing increases, and they are also less likely to be involved in delinquent behaviours. Good family relationships have spillover effects to other areas of the child’s life, including their education. Significant research in the education sector spanning the past 25 years has demonstrated that family involvement is critical to the educational success of children . Involvement in their children’s educational journey gives parents confidence, as they are able to see themselves as more capable of assisting educators or youth service providers who are working with their children. Inclusion makes parents and families feel valued and appreciated. Inclusion also sees parents as equal partners in their children’s education, and this gives them the confidence to assist with their children’s work and school projects that are to be completed outside of school. Family inclusion in education also sends a message to young people that their school values their parents’ contribution and involvement. All children want to feel pride in their families, and that pride will probably influence how the child feels about him/herself. When a Pacific individual is successful, whether it be in education, sports, or employment, families and communities celebrate together. Success for one individual is linked to family and community wellbeing; accordingly, most activities are carried out with the goal of “contributing to the family good, and not for personal gain”. As such, it is crucial that educators and service providers working with Pacific peoples ascertain the aspirations and expectations of Pacific families, so that their goals are aligned with those of Pacific families, ensuring maximum positive outcomes for the young person. This means a working together in partnership with families, sharing the responsibilities and decisions on the young person’s educational journey from start to finish. At TYMS, we always make a solemn promise to families that we will look after their children as if they were our own. As a provider of programmes aimed at addressing the underlying needs of young people through academic mentoring addressing education needs, values, life skills, physical fitness and cultural identity, TYMS works together with young people’s family and whanau, with the child at the centre. In the Samoan culture, when a precious gift such as an ‘ie toga (a precious, finely woven mat that is a most important item of cultural value in Samoa) is handed over, it is important that the receiver honour the gift. When families hand us their child, they are handing us their most precious gift. It is up to us to look after that gift, and we always make a solemn promise that we will look after their children as if they were our own. |

Categories

All

Archives

June 2018

|

What Our Clients Are Saying

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed