|

Author: Koleta Savaii Physical well-being is central to the fulfillment of our everyday tasks and long-term goals. We need to be in good physical health to be able to go to school or work and to participate in activities with our families and friends. In turn, we feel good about ourselves, we find enjoyment in what we do, and this has spill-over effects to other areas of our lives. It benefits society.

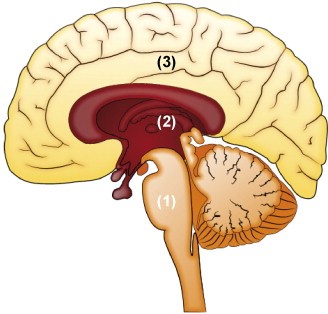

Improving the physical well-being of the young people who come to TYMS is a major goal of our service. We accomplish this through our focus on these two areas: the executive function and social cognition. The executive function and social cognition are associated with the prefrontal cortex which is situated in the frontal lobe part of the brain. The executive function is used to describe the capacity that allows us to control and coordinate our thoughts and behaviours. These skills include selective attention, decision-making, voluntary response inhibition, and working memory. Social cognition focuses on how people process, store, and apply information about other people and social situations. The way we think about others plays a major role in how we think, feel, and interact with the world around us. Puberty, which is associated with adolescence, represents a period of synaptic reorganisation in the brain (think of electrical wires in your computer reorganising themselves). Consequently, the brain might be more sensitive to experiential input at this period of time in the realm of executive function and social cognition. What this means is that, the adolescent brain is at a pruning stage which makes it an excellent time to foster executive function and social cognitive skills, which can last into adulthood. So, where does physical wellbeing come in? Physical activity requires volition, planning, purposive action, performance monitoring, and inhibition – skills associated with the executive function. To successfully adopt or change physical activity behaviour, an individual must form a conscious intention about what activity they wish to adopt (volition), identify the sequence of actions required to achieve the intended activity (planning), initiate and maintain focus on the chosen activity over time (purposive action), compare actual progress with planned progress over time, identify and correct mistakes (performance monitoring), and overcome the temptation to remain inactive or eat an unhealthy diet (inhibition). These are the stages our young people go through when we work with them on improving their physical well-being. The great thing about these skills is that they are transferable to other areas of life where planning, decision making, etc. are needed… like Maths. Research shows that kids who engage in physical activity significantly improve in Maths compared to kids who don’t. To improve social cognition, the literature suggests that accumulating social experiences is crucial for social cognitive processes. While we have a gym on site where young people carry out their exercise regimes, our mentors also spice things up by taking the young people out to parks, swimming pools, and local sports clubs. Given that majority of the young people who come to TYMS face social exclusion in one form or another, taking them out to the community aids in re-establishing their social connections, minimising their experiences of exclusion. When we are surrounded by lots of people, it is a learning ground for our social cognitive processes. We know anger, happiness, fear and joy because we see these emotions expressed on other’s faces or in their behaviour. And we know the boundaries to our own expressions of these emotions because others act as guides, expressing approval or disapproval when we behave or act in certain ways. Social connection fosters emotional intelligence and empathy, which are essential characteristics to being a good member of society. Here at TYMS, our approach to improving our young people’s physical well-being is holistic. It is about good physical health on top of fostering executive function and social cognition skills. These skills combined will enable our young people to reach their full potentials and secure positive futures.

0 Comments

Author: Koleta Savaii Adolescents are at a transitional stage – from their high dependence on parents and family to a need for autonomy and independence as they progress to adulthood.

While at this stage the role of the family in the adolescent’s life is secondary to that of the peer group, a close best friend, or a romantic partner, this does not mean family support is no longer needed. Adolescent researchers have established that different types of relationships fulfill specific interpersonal needs. For example, in romantic relationships, adolescents learn the social aspects of this type of relationship from their relationships with their parents and close friends (i.e., intimacy, conflict resolution, trust, empathy, and compassion), while the sexual aspects are learned from a dating partner. For healthy youth and consequently healthy adults, we need to ensure that every one of their relationships are healthy, and that they provide positive learning experiences. The adolescent years are also critical to the formation of one’s identity. At any point in history we will find that the opportunities available to youth for identity formation differ. For instance, for the grandparents of today’s youth, cultural exploration was restricted by geographical boundaries and the only cultures available was that of their families, church and communities. With increasing globalisation and the popularity of social media, today’s youth literally have access to thousands of cultures and opportunities for identification at their fingertips. A multitude of options to choose from can be distressing for any individual. But this can be especially stressful for adolescents whose brain areas that are responsible for executive function tasks (i.e. self-control, decision making) are not yet fully mature. This region of the brain is also responsible for a variety of other functions, its a common reservoir. Therefore, when we exercise self-control, we tax this common reservoir. For example, trying to maintain a healthy weight by exercising regularly and eating a healthy diet, while at the same time controlling the urge to eat unhealthy foods and stay in bed all day is physically taxing on this common reservoir. If it is not replenished (i.e. through positive self-affirmations, glucose consumption), then we are unable to exercise self-control in other areas of our lives (e.g. we procrastinate in our school work, or we over-spend beyond our available finances). Executive function is like a fuel tank that needs to stay filled. Positive self affirmation is one way of filling up our executive function tank. Adolescents are therefore at a stage in their lives where they need all the support they can get to keep them on track. Unfortunately, the availability of adults or other individuals willing to provide help and/or show interest in their problems is very limited. And this seems unfortunate, when an overview of the literature in this area shows clear links between the quality of adolescents’ supportive relationships with such features as self-esteem, suicidal and delinquent behaviours, emotional illness, and negative emotional states. The availability of positive social support is important, but this has to be accessible and of value to the individual. For example, in many Pacific families, gaining an education is highly valued. Generations of Pacific families have left their homelands for this very reason. For many Pacific parents, their motto is “Education is the key to a good life”. They wish for their children a life that they couldn’t experience themselves while growing up, so they push for their children to gain an education so that they can get good jobs to have a chance at the good life. Hence, adults in the community that provide mentoring and academic support is valuable to both Pacific youth and their families. Social support provided by parents and peers is crucial to the health and wellbeing of young people. This resource will not be utilised, however, if the barriers around access are not addressed. Barriers can include individual personality factors (e.g. low self-esteem), culture (e.g. cultural norms/attitudes around help-seeking), and financial (e.g. transportation costs). The availability of a valued resource coupled with the removal of barriers to accessing such resource, is key to ensuring young people are making use of the programs available to them within schools and in their communities. Social support whether it be provided by peers, parents, and members of the community is crucial to the health and wellbeing of young people. Positive adults who show an interest in youth and their problems is sometimes all it takes to keep a young person outside of prison, off the streets, and in school.

|

Categories

All

Archives

June 2018

|

What Our Clients Are Saying

|

Contact Us |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed